Jan 6, 2026

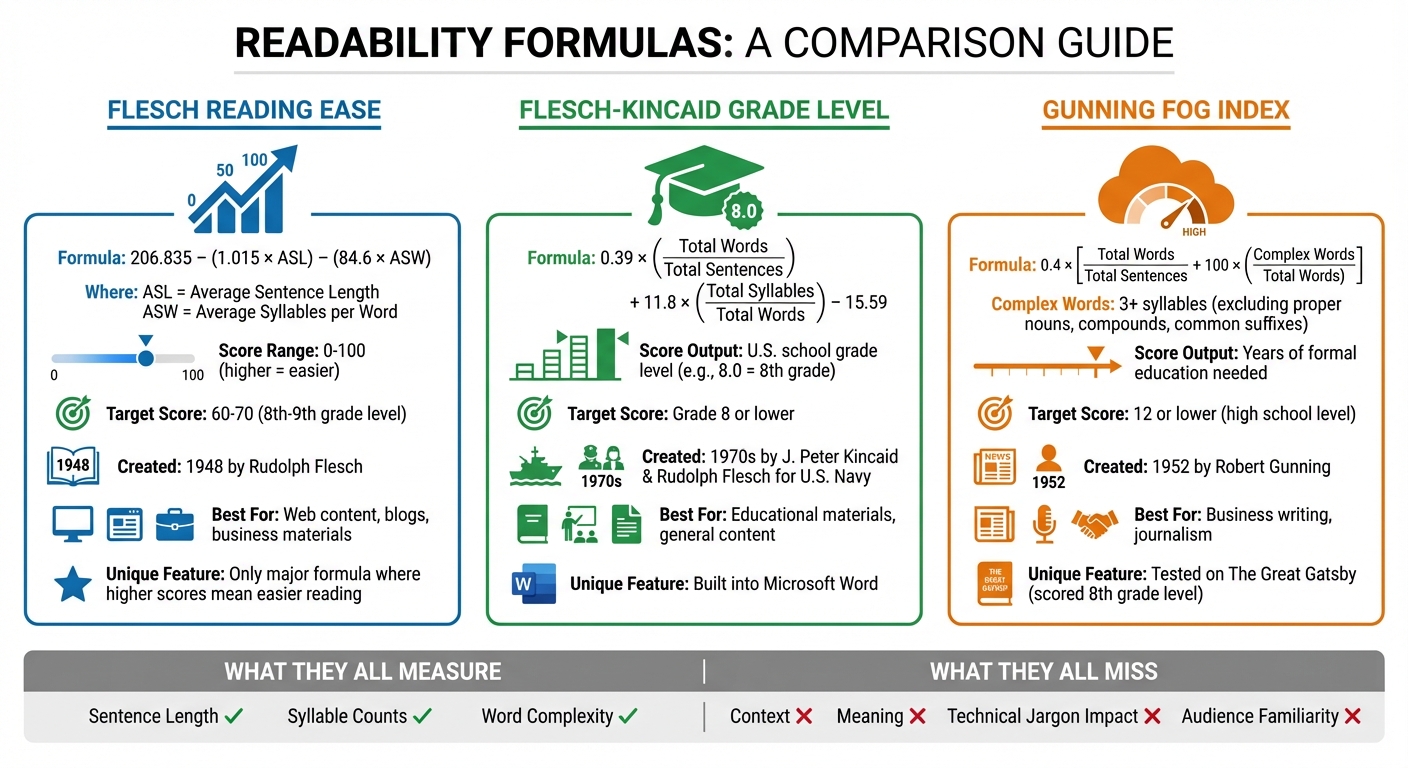

Rule-based readability algorithms use fixed formulas to measure how easy text is to read. They focus on sentence length, word complexity, and syllable counts to assign scores like grade levels or numerical ratings (e.g., 0–100). These systems are simple, consistent, and fast, but they ignore context, meaning, and audience familiarity. Popular examples include the Flesch Reading Ease, Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, and Gunning Fog Index.

Key points:

Readability tools are widely used in education, marketing, and content creation to improve text clarity. While helpful, they should be combined with other methods for better results.

Rule-based readability systems follow a structured and predictable approach. These systems rely on a fixed set of steps to analyze text.

"A system designed to achieve artificial intelligence (AI) via a model solely based on predetermined rules is known as a rule-based AI system. The makeup of this simple system comprises a set of human-coded rules that result in pre-defined outcomes." - WeAreBrain

The process begins with tokenization, which breaks the text into sentences and words while carefully identifying abbreviations and sentence boundaries.

Next, the system focuses on counting specific linguistic features. It tallies elements like syllables and letters using heuristic rules. For instance, vowel groups (a, e, i, o, u, y) are counted as one syllable, but certain suffixes like -es, -ed, and -e (except -le) are excluded. Words with three letters or fewer are automatically considered one syllable.

Finally, these counts are plugged into a linear mathematical formula. For example, the Flesch Reading Ease formula is:

F = 206.835 - 1.015 × (W/N) - 84.6 × (L/W),

where W represents total words, N is total sentences, and L is total syllables. The resulting score, usually between 0 and 100, reflects the text's readability level.

After tokenization and feature counting, these systems use these fixed formulas to assign a numerical value to text complexity.

Rule-based systems focus on what researchers refer to as "surface-level features" of text. These are measurable elements that don't require understanding the text's meaning.

Sentence length is a key metric. The algorithm calculates the average number of words per sentence, with longer sentences generally scoring as harder to read, regardless of their clarity or complexity.

Word complexity is another critical factor. Some formulas, like Flesch-Kincaid and SMOG, evaluate syllable counts - categorizing words with three or more syllables as difficult. Others, such as the Coleman-Liau Index, count characters or letters instead, as this is easier for computers to process accurately.

Some systems take it further by referencing pre-compiled word lists. The Dale-Chall formula, for instance, uses a list of 3,000 "familiar" words, assigning higher difficulty scores to texts containing words outside this list. Similarly, the Spache formula applies this method to texts for younger readers.

These algorithms are inherently rigid. They don't account for context, audience familiarity, or writing style. For example, a 25-word sentence filled with technical jargon will produce the same score whether it's intended for engineers or elementary students. While this rigidity ensures consistency and transparency, it also highlights their limitations.

Comparison of Major Readability Formulas: Flesch Reading Ease, Flesch-Kincaid, and Gunning Fog Index

The Flesch Reading Ease formula generates a score ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating easier readability. Unlike many other readability measures, where lower scores mean simpler text, this formula flips the script. Created in 1948 by Rudolph Flesch, a consultant for the Associated Press, the formula looks like this:

206.835 − (1.015 × ASL) − (84.6 × ASW)

Here’s what the variables mean: ASL is the Average Sentence Length, and ASW is the Average Syllables per Word. The constant 206.835 acts as a baseline, while deductions are applied for longer sentences and words with more syllables.

"Flesch suggested that shorter words with fewer syllables are easier to read and understand compared to longer, more complex words." - Brian Scott

A score between 60 and 70 indicates standard readability - texts at this level are typically suitable for readers at an 8th- or 9th-grade level. This range works well for most web content, blogs, and business materials.

That said, the formula doesn’t account for context or technical language. For example, a text filled with specialized jargon might score well but still feel challenging to a general audience.

The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL) transforms readability scores into U.S. school grade levels. For instance, a score of 8.0 means the text is understandable for someone with an 8th-grade education. Its formula is:

0.39 × (Total Words / Total Sentences) + 11.8 × (Total Syllables / Total Words) − 15.59

Developed in the 1970s by J. Peter Kincaid and Rudolph Flesch for the U.S. Navy, this formula uses the same core metrics as the Flesch Reading Ease but tweaks the coefficients to produce a grade-level result. For most content, aiming for a Grade 8 level or lower ensures better engagement.

This metric is also built into many word processors, like Microsoft Word, making it a handy tool for writers looking to fine-tune their content’s readability.

Next, we’ll dive into the Gunning Fog Index, which brings a different perspective to readability.

The Gunning Fog Index focuses on the complexity of words, specifically targeting those with three or more syllables. Developed in 1952 by Robert Gunning, the formula is:

0.4 × [(Total Words / Total Sentences) + 100 × (Complex Words / Total Words)]

It excludes proper nouns, compound words, and common suffixes like "-es" or "-ed" to avoid artificially inflating syllable counts. Independent clauses are treated as separate sentences.

"Much of this reading problem was a writing problem. His opinion was that public and business reading materials were full of 'fog' and unnecessary complexity." - Robert Gunning

Gunning famously tested his formula on The Great Gatsby, scoring it at an 8th-grade level - a result that aligns with expert literary assessments. The score corresponds to the number of years of formal education required to understand the text. For example, a score of 12 suggests high school senior-level comprehension, while anything above 17 points to graduate-level difficulty.

While the Gunning Fog Index is particularly useful in fields like business and journalism, where clarity is key, it has its limitations. Texts with short sentences but heavy jargon, or longer sentences packed with common multisyllabic words like "unfortunately" or "beautiful", can skew the results.

Let’s take a closer look at the strengths and shortcomings of rule-based algorithms, particularly in the context of readability assessments.

Rule-based readability formulas shine because of their simplicity and ease of use. You don’t need massive datasets or extensive training to get started - just input your text, and you’ll receive a straightforward, mathematical score. This makes them accessible to a wide range of users, from educators to marketers, who need quick insights into their writing.

Another key advantage is their clarity. For example, a Flesch-Kincaid score of 8.0 directly reflects factors like sentence length and syllable count. There’s no hidden complexity or "black box" logic involved. This transparency is why these formulas are still widely used today. Whether it’s the UK government, healthcare organizations, or marketing teams, many rely on these tools to ensure their content aligns with plain language standards.

Rule-based algorithms also work instantly on any text. Unlike machine learning models, which require extensive training on large datasets, these methods can analyze content right away. This makes them highly efficient and scalable for basic readability checks.

But, as with most things, simplicity comes at a cost.

The biggest limitation of rule-based formulas is their focus on surface-level features. They only measure things like sentence length and syllable counts, ignoring deeper aspects of meaning. A study from the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology highlights this issue, noting that such formulas are often outperformed by factors like word frequency, word length, and "surprisal" - a measure of how predictable a word is in its context.

"Differences in reading and comprehension ease do not have to lead to differences in reading comprehension performance, and vice versa." - Keren Gruteke Klein et al., Technion – Israel Institute of Technology

Another drawback is their inability to account for context or predictability. For instance, a word like "unfortunately" might lower your score because of its syllable count, even though most readers find it easy to understand. Conversely, a short sentence packed with technical jargon might score well but leave readers scratching their heads. Eye-tracking studies have shown that these formulas often fail to capture the actual cognitive effort a reader experiences.

There’s also the issue of topic bias. Research has found that these formulas can be heavily influenced by the subject matter of the text. For example, a medical article and a casual blog post might use similar sentence structures but receive vastly different scores simply because of their content.

Here’s a side-by-side look at how rule-based methods compare to data-driven approaches:

| Feature | Rule-Based Methods | Data-Driven/ML Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Interpretability | High; based on clear rules | Low; relies on complex models |

| Data Requirements | Minimal; works on any text | High; needs large datasets |

| Contextual Accuracy | Low; ignores meaning and flow | Higher; captures semantic nuances |

| Scalability | High for basic tasks | High but resource-intensive |

| Primary Metric | Surface-level features | Linguistic patterns and embeddings |

While rule-based algorithms have their limitations, they’re still a useful starting point. They provide quick, consistent feedback on basic issues like overly long sentences. However, it’s important not to rely on them as the ultimate measure of whether your content will resonate with readers. Instead, think of them as a helpful tool in a broader toolkit for creating effective, reader-friendly content.

Readability algorithms have found their way into various industries, shaping how we teach, write, and communicate. Whether in classrooms or marketing teams, these tools help tailor content complexity to the needs of specific audiences.

In education, readability formulas are indispensable for aligning reading materials with students' abilities. Teachers and educational technology platforms use these tools to ensure that content matches the skill levels of their learners. As Shazia Maqsood from the Institute of Computing at Kohat University of Science and Technology points out:

"Selecting and presenting a suitable collection of sentences for English Language Learners may play a vital role in enhancing their learning curve".

This approach allows educators to adapt materials effectively, making lessons more accessible. Beyond classrooms, these readability guidelines also influence broader content strategies aimed at making information more digestible.

For writers and marketers, readability tools act as valuable self-editing aids. Content written at a 6th-7th grade reading level often performs better, drawing more social media shares and backlinks. Blog posts, in particular, benefit from this approach, as simpler language tends to resonate with a wider audience.

The editing process typically involves identifying and simplifying complex words (those with three or more syllables) and reworking overly intricate sentences. Writers often favor active voice to improve clarity. Publishing houses also rely on readability metrics like Flesch-Kincaid or the Fry Readability Graph to ensure books align with readers' abilities. Similarly, the legal field has embraced Plain English standards after an American Bar Association survey revealed that 78% of respondents found legal documents too complicated to understand.

These traditional methods are now being adapted for use in AI-driven content creation.

AI platforms like NanoGPT incorporate readability algorithms to enhance the clarity of their outputs. For instance, NanoGPT generates an initial draft, which is then evaluated against readability metrics. If the draft falls short of the target, the AI revises it for improved clarity.

NanoGPT's OpenAI-compatible API (available at https://nano-gpt.com/api/v1/chat/completions) allows developers to programmatically generate text and automatically assess it using readability benchmarks. Adjusting parameters such as temperature - often set between 0.2 and 0.5 - can help produce more predictable and readable content.

However, a 2025 study involving 611 participants revealed some limitations. It found that traditional, modern, and AI-based readability methods, as well as two commercial systems, often showed low or non-significant correlations when measuring reading ease across different texts. The study highlighted that psycholinguistic measures, such as "surprisal" (which gauges how predictable a word is within its context), are better predictors of real-time reading difficulty. This suggests that while rule-based algorithms provide a solid framework for improving AI-generated content, they work best when paired with additional evaluation methods.

Rule-based readability algorithms rely on fixed formulas to evaluate how complex a text is, focusing on surface-level features like sentence length and word difficulty. Popular examples include the Flesch Reading Ease, Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, and the Gunning Fog Index, which use metrics like average syllables per word and the percentage of challenging words.

These tools have practical uses in various fields. In education, they help pair reading materials with students' skill levels. In healthcare, formulas like the SMOG Index are used to simplify patient instructions. Marketing teams also benefit from these metrics - readable content is shared on social media 58% more often than more complex articles.

Such insights provide a useful framework for enhancing text clarity.

While rule-based algorithms don't evaluate logic or flow, their simplicity and transparency make them helpful for writers. Instead of treating readability scores as strict rules, they can be used as practical guides. As Bruce W. Lee from the University of Pennsylvania explains:

"The tendency to opt for traditional readability formulas is likely due to their convenience and straightforwardness".

These tools offer immediate, actionable feedback by pointing out issues like overly long sentences or complicated vocabulary that can be adjusted for better clarity.

Think of readability scores as tools to refine your writing, not rigid standards to follow. Aim for an average sentence length of 14 words, and replace overly complex terms with simpler ones. Whether you're developing educational content, crafting marketing copy, or fine-tuning AI-generated text with platforms like NanoGPT, these algorithms are a practical way to ensure your writing resonates with your audience.

Rule-based readability algorithms rely on predefined formulas to measure how easy or difficult a text is to read. These formulas focus on surface-level features like sentence length, word complexity, and the use of longer words to generate a readability score. Common examples include Flesch Reading Ease and SMOG. Their simplicity and transparency make them easy to use, as they don’t require training data. However, they’re limited to analyzing only the basic characteristics of a text.

On the other hand, data-driven methods take a more advanced approach by using machine learning models trained on extensive datasets, such as comprehension tests or eye-tracking data. These models, including neural networks, dive deeper into text analysis, examining elements like syntax and semantics. While they can perform well in controlled environments, they sometimes fall short when applied to real-world scenarios, where simpler rule-based methods might still hold their ground.

So, while rule-based algorithms are easy to interpret and apply, data-driven techniques aim to explore deeper linguistic patterns - though they don’t always guarantee better results in practical applications.

Readability scores typically measure basic elements like sentence length, word complexity, or syllable count. But these metrics often overlook deeper factors, such as a reader’s prior knowledge, the complexity of the ideas being presented, or how logically the content is structured.

For instance, a brief sentence packed with technical jargon might be rated as “easy” by a readability tool, yet feel confusing to most readers. On the flip side, longer sentences with a clear flow and familiar language can be much easier to grasp. This highlights a key limitation of readability scores: they don’t always reflect how well readers will truly understand the material.

Rule-based readability algorithms work by analyzing straightforward metrics such as sentence length, word complexity, and syllable counts. While these methods can handle general texts fairly well, they often stumble when it comes to specialized content. For example, technical or medical documents frequently use complex terms that experts understand perfectly, but these algorithms flag them as difficult, skewing the readability scores.

One major drawback is that these algorithms are rooted in outdated models, often based on general texts from decades ago. They fail to reflect modern reading habits, like how people process information in context or skim for key details. As a result, their assessments can be unreliable, especially for niche audiences, such as non-native speakers or readers diving into highly technical material.

Another issue is their rigidity. These systems don’t automatically adjust to emerging fields like cybersecurity or genomics. Without manual updates, they struggle to evaluate content from these new areas, often leading to misleading results for specialized topics.